On the second weekend in May, a trip to Slaton, Texas, was in order. Has anyone ever said that? Why Slaton? A race (or for us, a run / jog), of course. The West Texas Running Club organized a run in Horseshoe Bend Canyon, a hole in the ground southeast of Lubbock. We signed up for the 11 mile distance, thinking that wouldn’t be too difficult after running a few half marathons earlier in the year. As a bonus, an event in West Texas would allow for a side trip to visit with a college student in Lubbock. The best laid plans …

Friday 2018 05 11

The Friday evening drive out to Slaton was uneventful, although we did catch the sunset behind this disproportional cow. Everything’s bigger in Texas, especially the cow statues guarding the thousand-acre ranches.

As mentioned, there was a member of the family attending school in Lubbock, so we’d had frequent trips to west Texas in the last few years. Most of those were focused on getting out and back in the shortest time possible, but this time we were able to try a new route – going west on 380. It was a long drive, but a nice change from the tried and true path on 114. West from Fort Worth, we passed through the small towns scattered along the highway – Throckmorton, Rule and Aspermont – all quiet on this Friday night.

When we searched lodging options in Slaton a few weeks prior to the trip, we discovered the perfect place – a tiny little apartment above a shuttered store right on the town square. We saved the home in our vacation list, and went back to reserve a week before the race (advance plans are difficult with kids and work schedules – you never know what might come up). Alas, the little apartment was booked. The only other person(s) in the world whose destination was Slaton on a random weekend in May had booked the place that we wanted. The only other option besides a random hotel on the road between Slaton and Lubbock turned out to be an old bed and breakfast next to the train tracks. While not our first choice, the Slaton Harvey House turned out to be a pretty cool spot.

This location in Slaton is not the only Harvey House. There are several, established in the early 1900s by one Fred Harvey, an English immigrant and frequent traveler who was not pleased with the dining options along American railroads (sounds like one of the travelers in our party… cough). A man who preferred a certain culinary standard, Mr. Harvey set out to fix this problem. The Santa Fe railroad accommodated his business proposal and helped fund his Harvey Houses, offering upscale dining and other amenities for rail passengers across the United States. These weren’t average restaurants or diners – these places were fancy (for the southwest United States in the early 1900s …). Meals were served on linen-topped tables accompanied by expensive silverware and fine china. Male diners were required to wear coats; extras were provided for those that arrived coatless. The locations were convenient as well, with the railroad providing a captive and steady audience. The Harvey Houses operated successfully until the Santa Fe Railroad, after funding Harvey’s startup, decided to offer dining cars on their trains. Why stop at the Harvey House when you can save time and enjoy a convenient “gourmet” meal while speeding down the tracks (at a whopping 40 miles per hour)? Most passengers opted to save time this way, and the Harvey Houses began to close down or were repurposed.

The Slaton Harvey House looked something like this when it was first built:

Entirely aside from the Slaton site, Fred Harvey’s dining establishments were the beginning of a new trend. He is credited with the start of the chain restaurant. We can thank him for McDonalds and Wendy’s, and… Hooters, and seemingly not just because it is also a chain. Beginning in 1883, he replaced his male waitstaff with women – a specific type of woman. Requirements for employment included females between the age of 18-30 only, possessing a certain look and being unmarried. They were known for their impeccable appearance, wearing perfectly starched aprons over dresses which accented their figures. The women lived in lodgings on the property, and took positions as servers, encouraged to interact with customers frequently. They were also required to remain unmarried for a least one year after being hired. His girls were the inspiration for the 1946 musical, The Harvey Girls, starring Judy Garland. This transition from Harvey House to Hooters reminds you of Idiocracy’s transition of Starbucks to … well, you really have to watch the movie. Mike Judge is a genius.

The Slaton House one of only six of the original eighteen Harvey Houses, and the only one that hosts overnight guests. It was rescued from pending demolition in 1989 by a passionate group of locals. We’re glad they went through the trouble. The Slaton House provided the perfect place to spend a weekend.

On the Friday night we arrived, we didn’t spend much time considering the history of the Harvey House. On our typical schedule, it was very late, and given an 11-mile run starting in a few hours, we just wanted a bed. A nice attendant without a figure enhancing outfit pointed us to our room upstairs in the northwest corner of the place, instructed us we were welcome to explore (with the exception of the basement), and told us goodnight.

Saturday 2018 05 12

It was early when we headed over to Horseshoe Bend Canyon for the run. Our bodies were tired from travel and lack of adequate sleep, but we’d paid to run, driven out to Slaton, and had nothing else to do … so we had to run. We actually showed up with plenty of time before the race start (unusual for these travelers), so we wandered a bit, checking out what we were told was a canyon.

The sun clearing the rim of the canyon showed typical West Texas ranch land – prickly bushes, scattered cactus, red dirt, and mesquite trees, diligently protected by miles of barbed wire fence. Given May in West Texas, it was chilly before the sun got up, but the x-rays of God beaming through zero humidity were a sign that this might be a long morning …

As time counted down, we squeezed in with the other runners, shaking off the last bit of sleep and brain fuzz. A non-dramatic start sent us towards the sunrise, with a flat run leading us to a steep uphill into the sun as we climbed out of Horseshoe Bend Canyon.

Despite the incline and the beams of sunshine blinding us, the scenery was desert pretty, and the temperature was not bad. Yet.

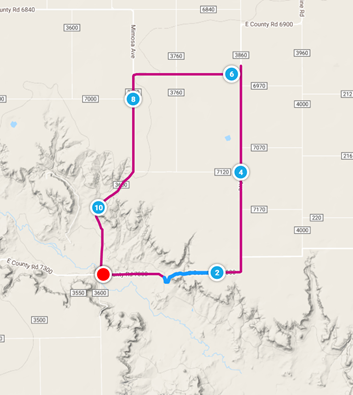

Having looked at but not internalized the course map, we cleared the top of the hill, turned left, and remembered we’d signed up for 11 miles in an area that includes a town called “Levelland”. The sun was shining down on our tired skulls and we were staring down four miles of straight, flat, West Texas roads.

While less engaging than say, Ithaca, NY, there was a level of Zen in just putting one foot in front of the other. Headphones on and zero traffic (or birds, or cows, or trees, or clouds …) around us, we made it to the next corner of this giant square we’d signed up for. Volunteers seemed happy to see us (maybe as a break from staring at empty cotton fields) and offered water.

Dividing 11 miles by 4 meant each leg of this square was going to be 3 miles or so – our second left showed us … more straight, flat, West Texas farm road. Left foot, right foot, hay foot, straw foot – we kept on trucking as the heat slowly dialed up. The cross-wind pushing on us from the south suggested this might turn into a more challenging event shortly. Passing the next water station, and making another left turn, we were reminded that West Texas is not just flat as a pancake. With nothing to stop the wind, well, that wind scours the area with gusto. Now we were bored, dusty, sweating, and moving at about half our prior pace as we tucked our heads down and thought about the miles to go. As we rolled into mile nine, the effort required to keep running just wasn’t worth it. Dropping to a walk, we conceded defeat – we’d break into a jog periodically just to get down to the finish line, but we were done with this hell-square of a run.

The last mile of the square descended into the canyon we’d climbed out of earlier, and the downhill encouraged us to shuffle a bit faster.

Eleven long, increasingly miserable miles after the start, we crossed the finish line. Somehow we averaged less than ten minutes per mile despite our ninth-mile stoppage. Tired, hot, and covered in grit, we dodged grasshoppers and weeds and cactus, and headed to the car.

We determined a nap was required to purge the memory of those eleven miles. Fortunately, the Harvey House has comfortable beds, dark blinds to keep out the Texas midday sun, and very quiet guests (us).

After an appropriately lengthy nap, we got in the elevator to head down to the main floor. There it was – the button labeled “B”. We remembered the host’s instructions – “the basement is off limits” – but like Curious George, that wasn’t going to stop us. It wasn’t like there was an “x” over the button, or a “danger, death awaits!” warning sign. So we pushed it, just to see what would happen. The tiny elevator creaked its way down the three floors, and once below the ground, slowly opened onto a very creepy and evidently forbidden space. Taking in an atypical damp, musty basement (these are very rare in Texas as a whole) with an old washing machine and then, in the corner – a floating broom. Of course.

Maybe the host’s instructions are intended to protect the guests from the ghost who likes to clean. Careful not to touch anything, we scooted back into the elevator, pressed “1”, and decided to pretend that never happened.

With a college student visit and dinner on the agenda for the evening, we took a quick drive through Slaton before heading up to Lubbock. At first glance, just another unassuming West Texas town, Slaton (like many of those other small towns) has history and character if you take the time to look. The town was designed in a wagon wheel fashion similar to Washington DC, where the streets reach outward in a circular format from the business areas of the community. The Santa Fe Railroad, which gave Fred Harvey his start, played a big part in the town’s early growth (as it did with many other spots across the desert Southwest). It was the only place of any size between Lubbock and Abilene; aside from ranchers and cotton farmers, many early settlers included railroad employees. By 1912 the town had a grown large enough to need a newspaper, a movie theatre, two banks and a hometown physician.

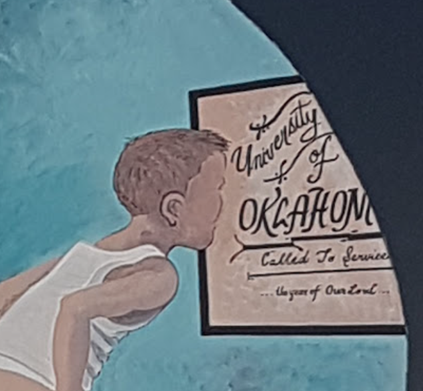

It doesn’t look like a mural that went up during that time, but we wondered if the first physician had anything to do with this work of art painted on the wall of a building on the square. Given the rather bizarre anatomy of both the doctor and his patient, we suspected someone else was responsible:

If the mural was intended as an advertisement to encourage new patients, we had to wonder about its effectiveness.

Farther down the road, we found some curious dining establishments. Klemke’s Barbecue was first, where cowboy Grandpa served fresh sausages right out of his hands to the hungry patrons. When searching for Klemke’s a few years later, the place didn’t show up on Google. Evidently it burned down about a year after our visit.

Across the street, we could acquire sea (lake? pond?) food – $8.99 for a catfish that resembles a whale with a crawfish arm on its lip. But only on Fridays.

Yoda’s Chicken Shack, resembling an old town dairy bar, appeared to be closed this day (the day of our Lord?), and possibly forever. We tried to envision Jedi techniques for frying chicken, but gave up.

Research on Slaton also brought to our attention that this was the home of the namesake of the song “Peggy Sue”, released by Buddy Holly, a Lubbock native, in the 1950s. She was the girlfriend of Jerry Allison at the time, the drummer for Buddy Holly and the Crickets.

Should we decide to make Slaton our permanent residence, apartments are available on “Nineth” Street. With kitchenettes.

We headed north out of Slaton, with vague plans to find dinner somewhere close to Lubbock. After some conversation with the college student, we agreed to meet at Farm to Fork, a place that popped up on Google located just east of Lubbock and north of Slaton, in a neighborhood called Ransom Canyon. For a random find, it was perfect. Fresh food, excellent drinks and good atmosphere. Sadly, it seems the restaurant didn’t survive through the pandemic – the doors were closed and the lights out on our next visit a few years later.

Before returning to the home of Peggy Sue, a quick tour around Ransom Canyon was in order. Over the course of the day, we’d run out of and into Horseshoe Bend Canyon. One of us claims a high school hometown of Canyon, Texas. We’ve spent time in Palo Duro Canyon and Caprock Canyon State Park. All of these canyons are located in West Texas, which for the uninitiated is confusingly counterintuitive – West Texas is supposed to be the home of endlessly monotonous flatlands with cows and wind and cotton, not canyons. While not on the scale of the Grand Canyon, the terrain available out here is worth exploring, even if it takes time to find it.

Ransom Canyon was a typical break at the edge of the Caprock where hundreds of thousands of years of intermittent rainstorms and wind-driven erosion have created meandering draws and cliffs. This one was dammed to create a recreational lake surrounded by residential neighborhoods and a wide variety of homes, some tiny and some in the million-dollar-plus range. Among all the variety, there’s one especially unique home. The Bruno House is a residence constructed entirely of steel perched on the cliffside, affording very nice views of Ransom Canyon and the neighbors.

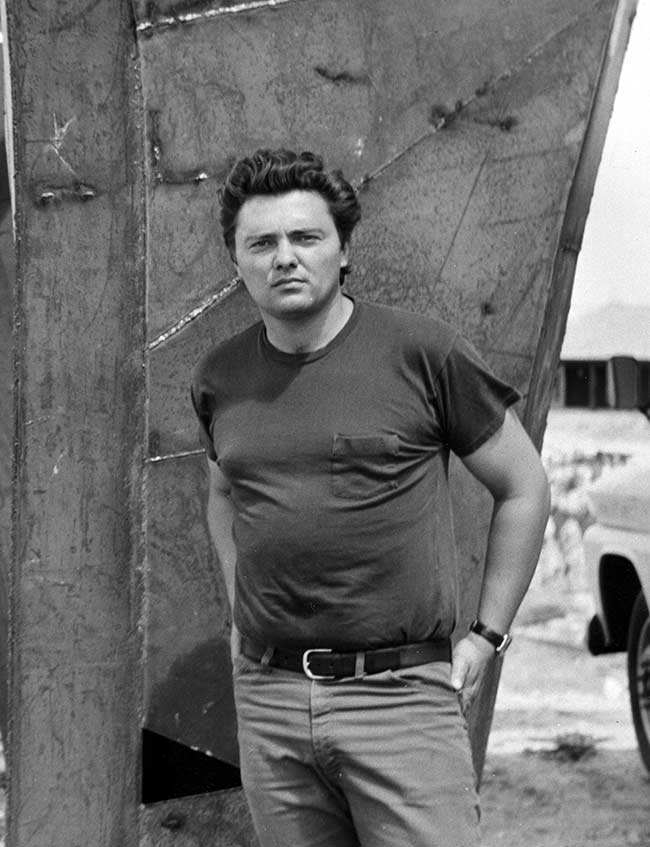

Probably unique in the world, this was a project taken on by a Lubbock transplant. Originally from California, Robert Bruno relocated to Lubbock with his family to take a job teaching architecture at Texas Tech University. It didn’t matter that he wasn’t trained in architecture; the school was in its early stages and standards weren’t quite as high. His background was actually in sculpture, and he was obviously very talented. He wasn’t particularly interested in his teaching job, but he was very interested in building a house on a plot sitting over Ransom Canyon. Featuring unusual angles and stained-glass windows, it’s a been a place of interest for years.

What we imagined Robert Bruno must look like:

What he actually looked like:

In addition to his Steel Castle, Bruno designed another house in the neighborhood known as the Flintstones House – we didn’t find that one, but will look for it on our next trip to the canyon …

Despite decades of work, starting in 1973, Bruno never finished his complicated project. He moved into the unfinished building for the last few months of his life, simply because he knew it would be his only opportunity to live there. After his death in 2008, his daughter took over the estate, and it was sold at some point. There were rumors that it would become an Airbnb, but that hasn’t happened as of yet. Bruno had also intended at one point to line the interior walls with nude torsos to cover the exposed steel, but he never got around to that either. This Texas Monthly article has some further details (and better pictures to boot).

Having sufficiently explored Ransom Canyon, and the Bruno house, we headed south to Slaton, watching the light and clouds shift across the endless horizon.

Arriving in Slaton, the wide open skies got a bit more cluttered with power lines and water towers and grain storage, but the colors and pageantry of the West Texas sky still shone. A long day eventually ended with some well-deserved sleep.

Friday 2018 05 13

Our room at the Harvey House was full of books. Waking up early for no particular reason (hello, old age) one of us spent some time trying to enjoy a satire about Texas written by a New York native which lost its shine quickly after a decently funny start. There’s only so much snarky humor about Texas stereotypes that you can squeeze into a book before it starts to sound ridiculous. Another guest at some point had made some progress through the Yankee jokes, leaving a curious bookmark stuck in the middle pages. Examining the scrap of paper revealed it was a coupon for some Diet Pepsi which expired on December 31st, 1986.

We guessed that might have been the last time the book had been opened.

The attentive Harvey House host prepared breakfast for us before we headed out, a nicely prepared spread of eggs and vegetables, yogurt and fruit, along with coffee and juice. Not necessarily a Michelin-starred experience, but certainly sufficient for two random visitors from DFW. Packing up, we thanked our hosts and got ready for what promised to be a hot and dusty drive home. Which way to take? We always have to balance between desire to explore and the need to get home and act like responsible adults.

Driving by the railyard before getting in the car, the trains probably look different than they did when Harvey House was established.

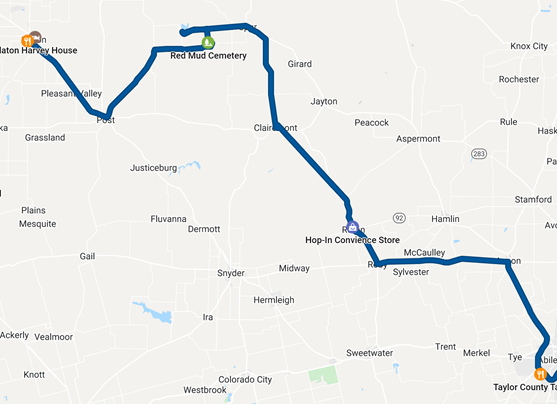

Even for us, the route home was disjointed and unorganized. The first part took us through Clairemont to Abilene, with a stop at the Red Mud Cemetery for some sunny and hot exploration of the graveyard.

Professional signage is such a waste of time …

Originally known as Tap Cemetery, this burial ground began when a Mr. Barger was buried on his own land near the house he’d occupied. It wasn’t a natural death – he was murdered by a Mr. Jess Adamson after some sort of controversy. This seems typical of the 1800s – don’t like the guy? Take him out. Mr. Barger’s widow passed away the same year of tuberculosis and was laid to rest next to her murdered husband. Shortly after, others in the town started to lay their loved ones to rest near the Bargers. Having explored the land surrounding this plot, it must have seemed like as good a place as any. Walking around the huge red ants covering the hot, rock-hard ground on this day, we wondered how they were able to dig even a foot into the ground. As George Dunham would say, it seem … impossible.

We wondered if Mr. Smith or his wife might have escaped from their tomb, but realized any zombies who’d made it into this baking sunlight would have turned into zombie jerky and therefore be no threat to us. Whew.

In 1910, a schoolhouse was constructed nearby with a red roof, and the cemetery was renamed Red Top – not sure if there was a link or merely coincidence. The red and yellow leaves of the plastic grave decorations stuffed in the red trash barrel continued the theme …

Later, after the Red Top School building was relocated, locals began referring to the graveyard as Red Mud, and the name stuck.

We left the cemetery, hoping not to encounter W.A. Smith (maybe he is the ghost who manages floating brooms in the Harvey House basement). It was time to wander down some more dirt roads in the middle of nowhere.

The roads transformed from dried and windswept mud and dust to paved soon as we headed in the general direction of Abilene. Unsurprisingly, much of the road looked like …

Traveling on the backroads is always interesting. We realize we are very much in the minority on this opinion. Not another car for miles. Ever the explorers, we spotted this distinctive old building seemingly abandoned by the highway, and decided we had to go back and check it out.

As is evident by the mud bricks and iron bars in the windows this place has been around a while. Sitting in the ghost town of Clairemont, this building originally served as the Kent County Jail. According to the historical marker nearby, it was constructed in 1895, three years after Clairemont was established. The jail was one of several structures in town, which included a few stores, a bank, a newspaper and a hotel (we’re detecting a theme in small West Texas towns). Clairemont was thriving at the time, with booming cotton and cattle ranching businesses. Given the timelines for decline, it seems likely that the Dust Bowl that blasted through Texas in the mid and late 1930s, helped push the town into ghost town status, and the brutal droughts of the 1950s put the final nails in the coffin. The population was around 15 orphaned souls going into the 2000s.

We wandered through the jail (it was open at the time to curious travelers). The Kent County Jail is proud of its claim to fame – no attempted escapes ended in success while it was in operation. It was said to be one of the most difficult jails to break out of. The most common prisoners, according to the historical marker, were horse thieves, moonshiners and murderers. Looking around inside, it appears to be a frequent spot for local vandals to do their thing now that the risk of incarceration has passed.

According to anecdotes and recollections from visitors and area residents, this was one of the only jails that allowed the jailers to lock or unlock the several cells at once from a single mechanical lever. Considering the mechanics, this would seem to increase escape opportunities, but we’re not prison designers.

There’s a nice view out of this cell’s window – a car with bikes attached. Walking back to the car, we were reminded of a missed activity: ride the bikes. We always bring them along, with expectations that we will include a ride at some point in the trip. The day was quickly passing by, and we still had dinner and a three-plus hour drive left. It just wasn’t meant to be on this weekend.

The jail was our last stop of interest, as it was time for dinner and beverages, earned by our long day in the Texas sun. We headed to Abilene for a meal at one our favorites: The Taylor County Taphouse. Having discovered this during one of our many biking and exploration trips, the excellent selection of beers, well-made cocktails, and solid dinner (and brunch and lunch) menu keep us coming back.

The weekend felt complete. We did all the things: ran nine miserable miles and walked two for our eleven mile jaunt, discovered a new town and learned some history, met up and entertained the college student, visited buildings built out of steel and buildings built out of dirt, checked in with some graveyards, and wrapped it up with beer and dinner. Everything except biking – we never rode bikes. We need more hours in our days. Promising to do better on the next trip, we switched on the cruise control, followed the expressway east and drove home.